Introduction

The start of the 2021-2022 school year marked the 50th anniversary of the pairing of Hale and Field Elementary in South Minneapolis. This controversial initiative to combat racial segregation in the district polarized the city and had a significant impact on the lives of those involved. Separate Not Equal pays tribute to the parents and educators who fought for desegregation, celebrates the students who attended these schools, and encourages guests to reflect on the state of our school system today.

Pairing Proposal

“We felt pairing was an excellent, and proper, first step toward achieving an ideal racial balance…This way we are not separating neighborhood children: we are not busing any of them a great distance, and we are preserving the sense of neighborhood schools.” -John B. Davis, Superintendent of Minneapolis Public Schools, quoted in the New York Times, September 16, 1971.

“Pairing” is the merging of two schools so that each school serves different age levels for a new and larger attendance area. This was an innovative concept in 1970 when the Minneapolis School Board proposed turning Hale Elementary into a primary school for K-3 students and converting Field Elementary into an intermediate center for grades 4-6.

Pairing was designed to combat segregation. Students of color made up 13% of elementary age students in Minneapolis, but most schools in the city were segregated, including the adjacent neighborhood schools of Hale and Field. Hale’s students were 98% white, while about a mile and a half away, Field’s enrollment was 57% students of color, mostly Black.

At the time, there was already ample evidence that racial and socio-economic isolation has a negative effect on the attitudes, human understanding, and academic achievement of school age children. Field was over capacity and under-funded, while Hale was under capacity and well-funded. For these reasons, the Minneapolis School District identified Hale and Field as candidates for pairing.

Located on 13th Ave South in Minneapolis, Hale Elementary was built in 1930.

Field Elementary was built in 1920 and is located on 4th Ave South in Minneapolis.

Segregation in South Minneapolis

“Racial isolation is a problem in Minneapolis.” -Urban Center for Quality Integrated Education Dissemination Report, 1975

In 1970, more than 90% of the city’s Black residents lived in 10% of the city, mainly in concentrations north and south of downtown. Though segregation was not legally mandated as in southern states, it was enforced by racially restrictive housing deeds and redlining. This ensured that white residents and Black residents did not occupy the same spaces. Minnehaha Creek in South Minneapolis served as the boundary separating the nearly all-white Hale neighborhood from the mostly Black Field community. Residents came to call Minnehaha Creek the “Mason-Dixon Line.”

Though you would not find any “whites only" signs, there were designated white establishments in the Hale neighborhood and Black establishments in the Field neighborhood. An unspoken rule dictated that unless you were in “mixed” company, residents would go to their respective places according to their race.

Community members recall that white Hale students played at Pearl Park, no matter their home’s proximity to McRae Park, which was designated for the Field community. After a McRae-Pearl football game at Pearl Park, Hale families would go to the Dairy Queen three blocks away, whereas Field families went to a Dairy Queen a mile away on 38th Street.

Aerial image of Pearl Park, ca. 1970s.

Courtesy of Minneapolis Park & Recreation Board

Children on the playground in McRae Park in 1975. J

Jeffrey P. Grosscup Photograph Collection, Hennepin County Library

Opposition

“From the beginning of time people have associated with their own kind whether it be on an economic, educational, nationality, ethnic or other level. Forcing people of unlike moral and economic backgrounds to live together will only spell trouble.” - Excerpt of letter from Hale parent to Minneapolis Board of Education, March 1971.

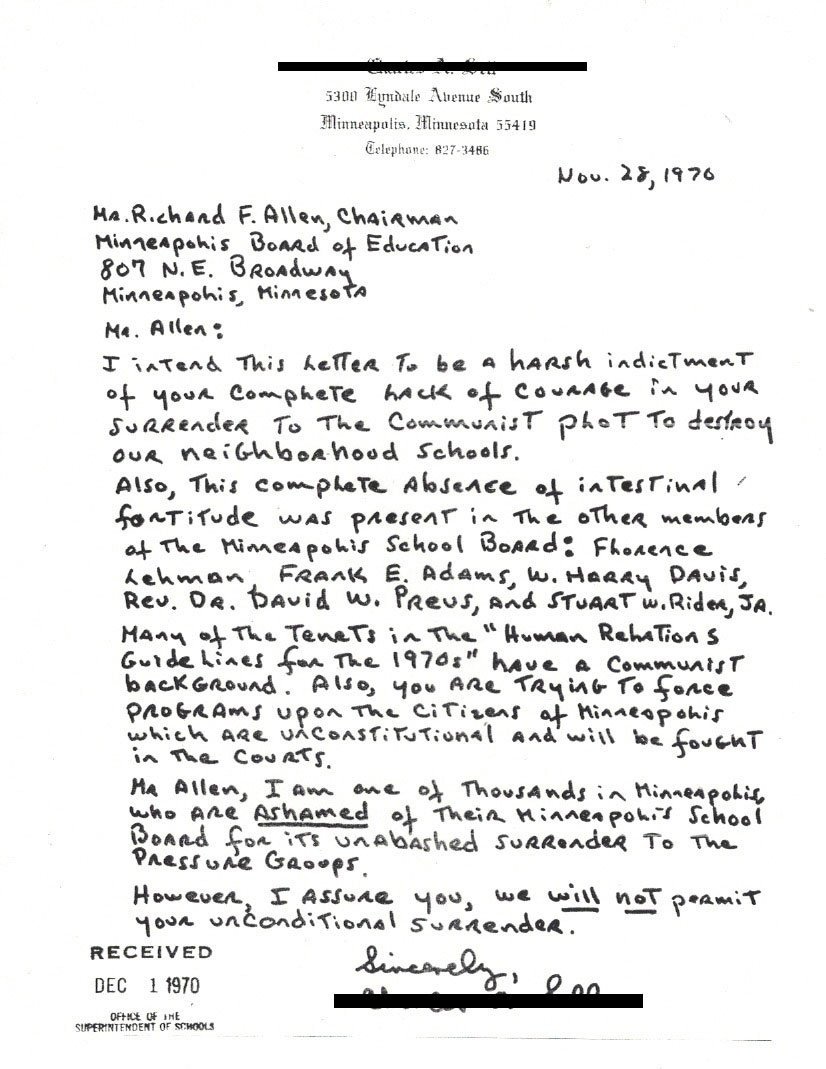

At Hale, 70% of families opposed pairing. To block it, they organized a group called the Concerned Parents of Hale, which joined forces with segregationists across the city, including Mayor Charles Stenvig. They stood vehemently against school desegregation, though publicly they argued they were merely “anti-busing.” Other opponents claimed the pairing was a communist plot.

Segregationists made school board meetings intensely contentious. After the meeting that proposed pairing, Superintendent John B. Davis, and board member W. Harry Davis (no relation) received so many threatening phone calls that both their homes were put under police surveillance. Opponents also collected 2,200 signatures for an anti-pairing petition. Due to their efforts, bills were introduced in the Minnesota State Legislature to dissolve the Minneapolis School Board, and a class action lawsuit was filed.

Some parents at Hale also attempted to enroll their children in local private schools. To discourage this, Monsignor Richard Doherty of the Resurrection Catholic School, located across the street from Hale, announced he would not admit new students who were not already members of the church. Doherty asserted, “I didn’t want it to be a haven for racists.”

Field parents had no organized opposition to the pairing. For many Black parents, their largest concern was for the safety of their children in the hostile Hale neighborhood. This fear was substantiated by the school district, which made an exception to its busing policy to allow all students from the Field neighborhood to be bused to Hale, regardless of distance. This was one effort to safeguard them from the “antagonistic neighborhood across the creek” where they “would be subject to harassment.”

Segregationists attend a Minneapolis School Board meeting on March 14th 1972. Film still of KSTP news clip from the KSTP TV News Archive, courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society.

A letter written to the Minneapolis School Board in opposition to school desegregation. Many letters claimed the pairing of Hale and Field was a communist plot.

Support

“I wanted people to know that our children were just as bright and capable of learning, but they had to have all of the right books and education. So when [they] came along with the pairing idea, why wouldn’t I jump on board?” -Mrs. Alberta Johnson, pairing advocate, teacher’s aide, and mother of five Hale-Field students, 2017.

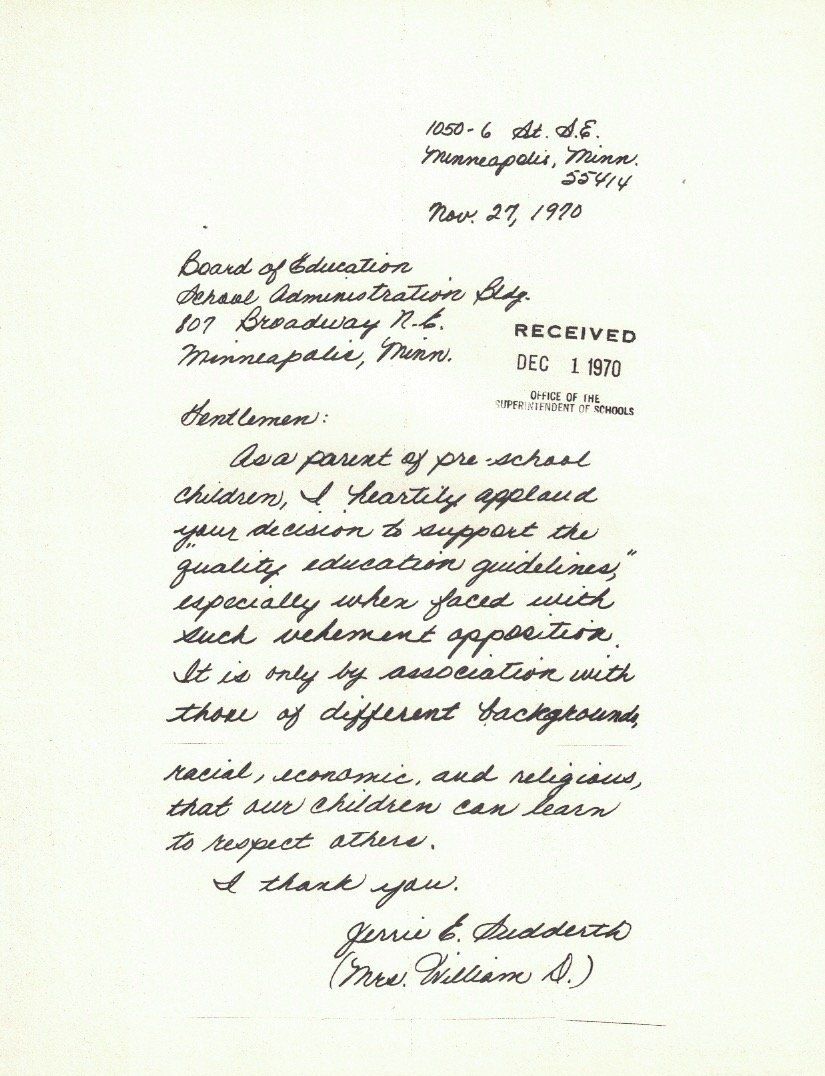

Due to the controversial nature of the pairing proposal, a two-year campaign by Black and white parents from both Hale and Field communities was essential to the success of the project. To clearly explain the benefits of pairing, materials were distributed to parents that explained how it would improve their child’s education by bringing students of different races together and by introducing a new, more equitable, educational program.

Since the source of most of the opposition to the pairing proposal came from Hale parents, this is where pairing supporters focused their efforts. The Hale PTA was divided on the issue of pairing, and the school district itself was largely uninvolved, so pairing advocates formed an independent group called Hale Neighbors for Improved Education.

Proponents found that small, informal coffee parties were an effective way to educate the community. These coffee parties allowed for constructive dialogue, as opposed to large public meetings where the loudest segregationist in the room could dominate the discussion. They held thirty coffee parties, each with some Field parents in attendance along with a representative from the Minneapolis School Board. In another effort to gain support, Hale parents also established a telephone hotline to disseminate information to parents who were unable or unwilling to attend a coffee party.

In the end, these desegregation pioneers were successful in securing approval for the proposal and in building relationships between Field and Hale parents that allowed the pairing to move forward. They had laid the groundwork for success; now they waited to see what would happen next.

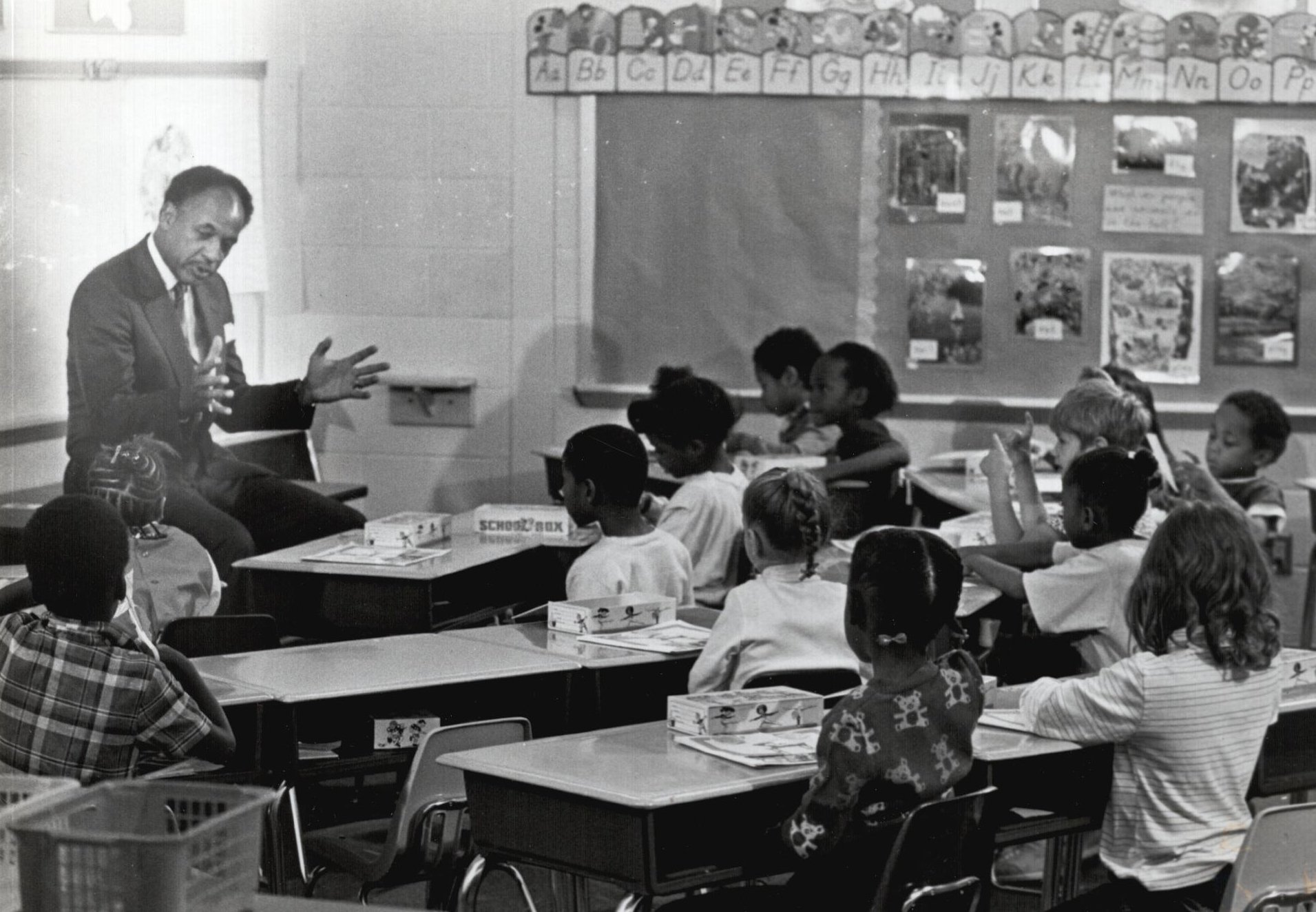

Dr. John B. Davis, Jr. (1921-2011), Superintendent of Minneapolis Public Schools, and advocate for desegregation, speaks at a public hearing about Minnesota's proposed guidelines for racial balance in schools, November 15, 1969.

Photo by Powell Krueger, Minneapolis Tribune. Copyright 1969 Star Tribune.

A letter written to the Minneapolis School Board in support of desegregation.

W. Harry Davis, Sr. (1923-2006) was a renowned Minneapolis civil rights activist, business man, and civic leader. Davis joined the Minneapolis School Board in 1969 as an advocate for desegregation. In 1971, he ran as the city’s first Black mayoral candidate. In his lifetime, he received seventy-nine civic leadership awards.

The First Day of School

“We didn’t have a single tear, and that’s unusual for a kindergarten.” -Gladys Anderson, Principal of Hale School, quoted in the Minneapolis Star, September 2, 1971.

“It went beautifully-just great. We’ve had almost no problems. The only things wrong were a kid not finding his room or a parent not knowing where the bus stop was.” -Bradley A. Bentson, Principal of Field School, quoted in the Minneapolis Tribune, September 3, 1971.

Many adults were legitimately concerned that a racially motivated, violent incident would occur on the first day of pairing in September 1971. Some Field parents followed their children’s bus to school to ensure they made it safely inside. However, most students were just concerned about finding their new classroom or riding a school bus for the first time.

At each school, parent volunteers and members of the School Board arrived early to welcome students. Members of the press were also present but, as their cameras rolled, the school day started without incident. The desegregation of Hale and Field occurred successfully that first day as both student populations became 30% students of color.

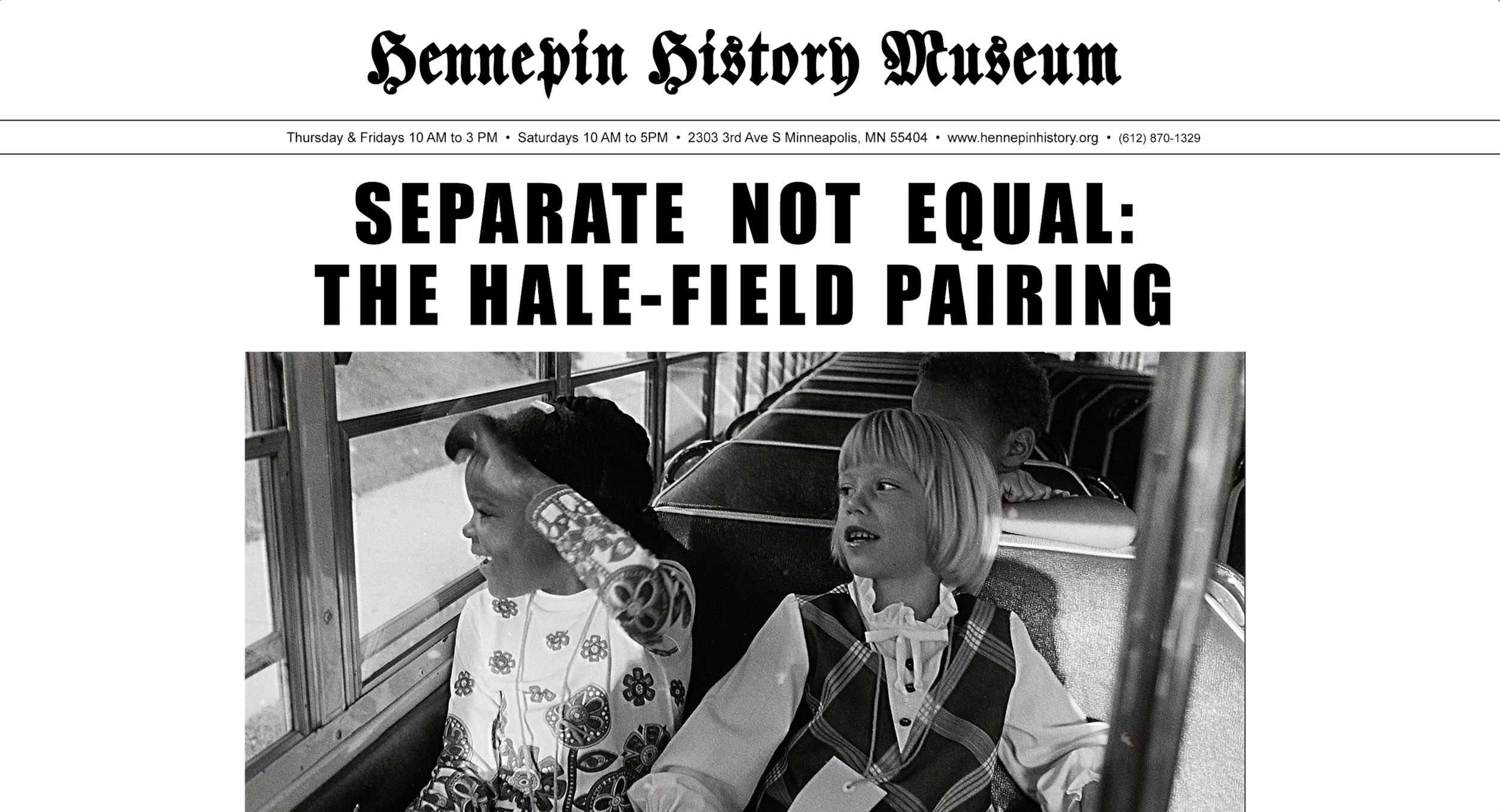

Monica Lash and Molly Johnson were among the first students picked up on the first day of school. Image from the Minneapolis Star, September 2, 1971.

Courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society

A desegregated classroom at Field Elementary, ca. 1972.

Courtesy of Heidi Adelsman.

Mrs. Bessie Griffin worked for Minneapolis Public Schools for thirty years, and was a teacher in the Gold Unit at Field from 1971 to 1996.

Courtesy of Heidi Adelsman.

Continuous Progress Curriculum

Desegregation alone was not enough. The pairing also aimed to make students’ learning experiences more equitable. First, both schools added support staff, including teachers' aides, social workers, and counselors. The schools also required that at least 10% of staff be non-white. Many new hires were mothers of students from the Field neighborhood, which further established new connections in both communities.

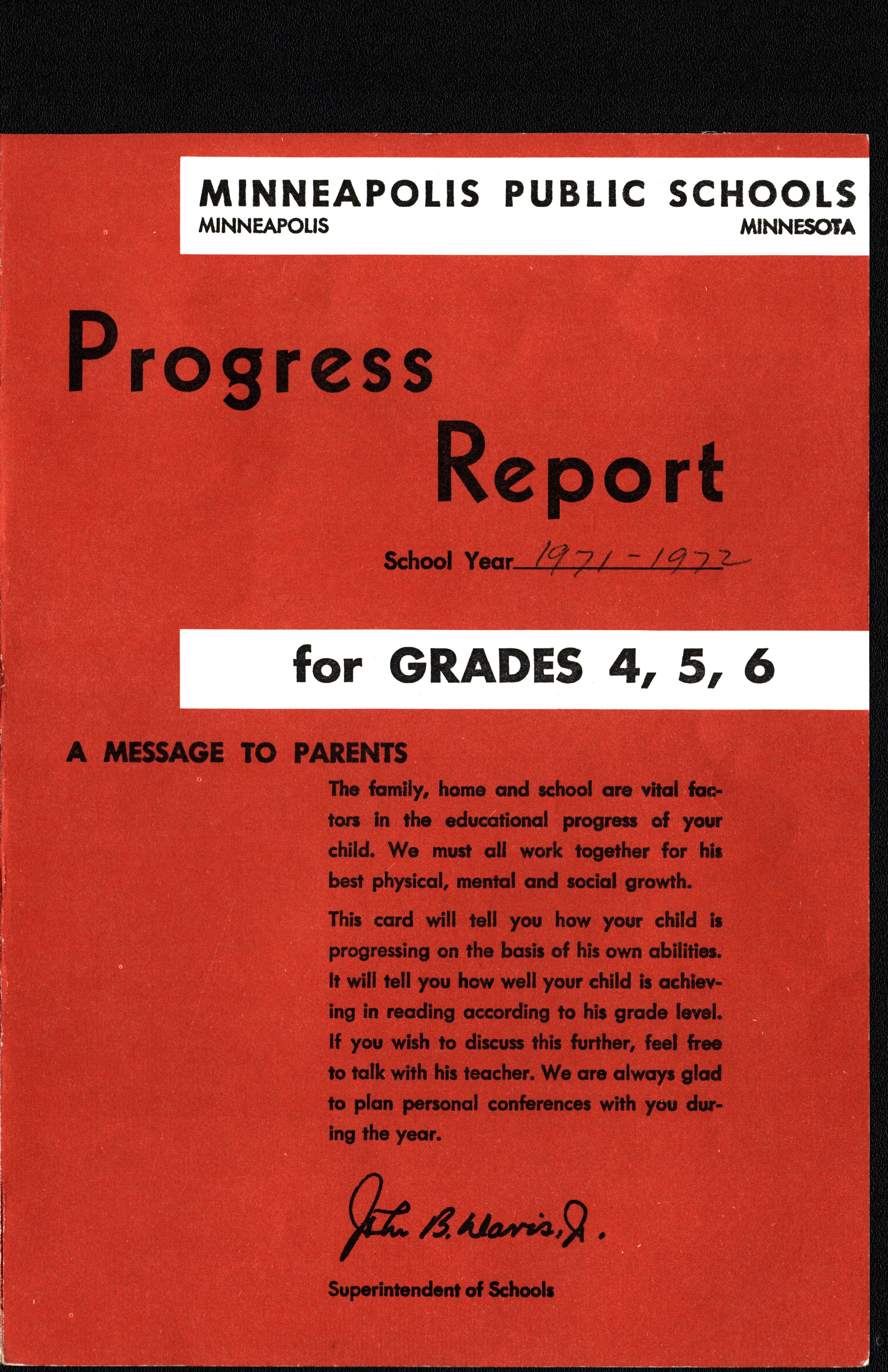

Hale and Field also adopted an innovative, flexible, non-graded educational program, which used a team-teaching approach focused on individualized instruction. This allowed students to progress at their own pace. Instead of single-grade fixed-curriculum classrooms, students were placed into “units” that accommodated their needs.

By narrowing the age range of each school, both Field and Hale were also able to expand their curriculum to not only focus on basic skills, but also on social and intercultural learning. Students explored their individual talents and interests through elective courses called “option classes,” which included photography, computers, foreign languages, cooking, music, carpentry, and Black history.

These progress reports (Progress Report 1 & Progress Report 2) from the 1971-1972 school year replaced traditional report cards under the new “Continuous Progress Curriculum.”

Courtesy of Heidi Adelsman

Progress Report 2

Progress Report 1

Mr. James (Mike) Andrews, pictured here with students in a woodworking class, worked for Minneapolis Public Schools for thirty years, and was a teacher at Field from 1971 to 1989.

Photo by Powell Krueger, Minneapolis Tribune, December 19, 1971. Copyright 1971 Star Tribune

Outcomes

"The basic benefit [of desegregation] is coming to know someone who exists outside your frame of reference...the breakdown of the fear and stereotypes and myths that people have about other people, and that goes across racial lines...One of the other pluses is to do away with the distinction that is perpetuated by some researchers that whites suffer academically when they move into a desegregated setting...or the other myth is that blacks learns more when they sit in a classroom with whites." -Dr. Richard Green, speaking on the advisory committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1976

Whichever method one might use to measure the success of the Hale-Field pairing, it is undeniable that it was a victory over school segregation in Minneapolis at that time. The project accomplished all its objectives, including maintaining or improving the education of students, eliminating racial isolation, and combating stereotyped attitudes on race by both white and Black students.

Because the pairing was a groundbreaking and federally funded initiative, it was the subject of many surveys, studies, and reports after its initial three-year pilot program. Achievement tests confirmed that students at both schools were performing equal to or better than the city-wide average. Moreover, surveys found that students showed an increase in self-esteem and a preference for desegregated classrooms.

When Field and Hale parents were surveyed in the 1973-1974 school year, 90% of them said their children were getting a good education, and 75% said they thought pairing was a good idea. They cited more positive than negative experiences their children had because of pairing: “The positive experiences most frequently revolved around being exposed to children of different backgrounds, the quality of teachers, and the wide variety of educational opportunities.” Student enrollment also proved success. Though at the onset of pairing, 235 students transferred out of Hale and Field, by 1974, 289 students had voluntarily transferred into the schools, and 36 more were on a waiting list.

Dr. Lowery Johnson was principal at Field from 1974 to 1979, he worked for Minneapolis Public Schools for over thirty years, and served as principal at seven schools around the city.

Courtesy of Heidi Adelsman

A track and field day event at Field Elementary at the end of the first school year of pairing, 1972. The events included softball throw, high and long jump, relays, 50 yard dash, and long distance running.

Courtesy of Heidi Adelsman

Dr. Richard Green (1936-1989) worked in education for thirty years as teacher, principal, and in 1980 became the first Black superintendent of Minneapolis Public Schools. In 1988, he became the first Black chancellor of New York City Public Schools.

Courtesy of Sherri Green.Courtesy of Kelley, Kim, and Sherri Green

Today

The Hale-Field pairing paved the way for desegregation efforts across Minneapolis. It was followed by over a decade of federal supervision to ensure the entire school district took affirmative action to combat segregation. However, today, most of the Field neighborhood is white, which is reflected in the current enrollment at both schools. Moreover, schools have resegregated across the city.

Unfortunately, today, Minneapolis is one of the most segregated school districts in the nation, with one of the widest achievement gaps based on race. Numerous factors have led to this situation, including changing demographics and the introduction of charter schools. Nonetheless, one thing remains constant: the importance and value of equitable educational opportunities. Thanks to the efforts of the pioneers who wanted a better future for children, fifty years later the Hale-Field pairing is celebrated as one victory in the fight against segregation.

Special Thanks

Separate Not Equal: The Hale-Field Pairing is a community-based public history collaboration including Heidi Adelsman, Daniel Bergin, Cindy Booker, Hannah Coble, Acoma Gaither, Sophie Hunt, Alyssa Thiede, and Carissa Thomas.

This project is supported by Minnesota Transform, a Mellon Foundation Just Futures Initiative, The Heritage Studies and Public History program at the University of Minnesota, and the Hennepin History Museum.

This website was designed by Chufue Yang, an undergraduate student at the University of Minnesota pursuing his BFA in Graphic Design. Under the employment of the Digital Arts, Sciences, and Humanities (DASH), and the Liberal Arts Technologies and Innovation Services (LATIS), Yang created this website in collaboration with the Hennepin History Museum spring semester of 2022. More on Chufue’s experience here.